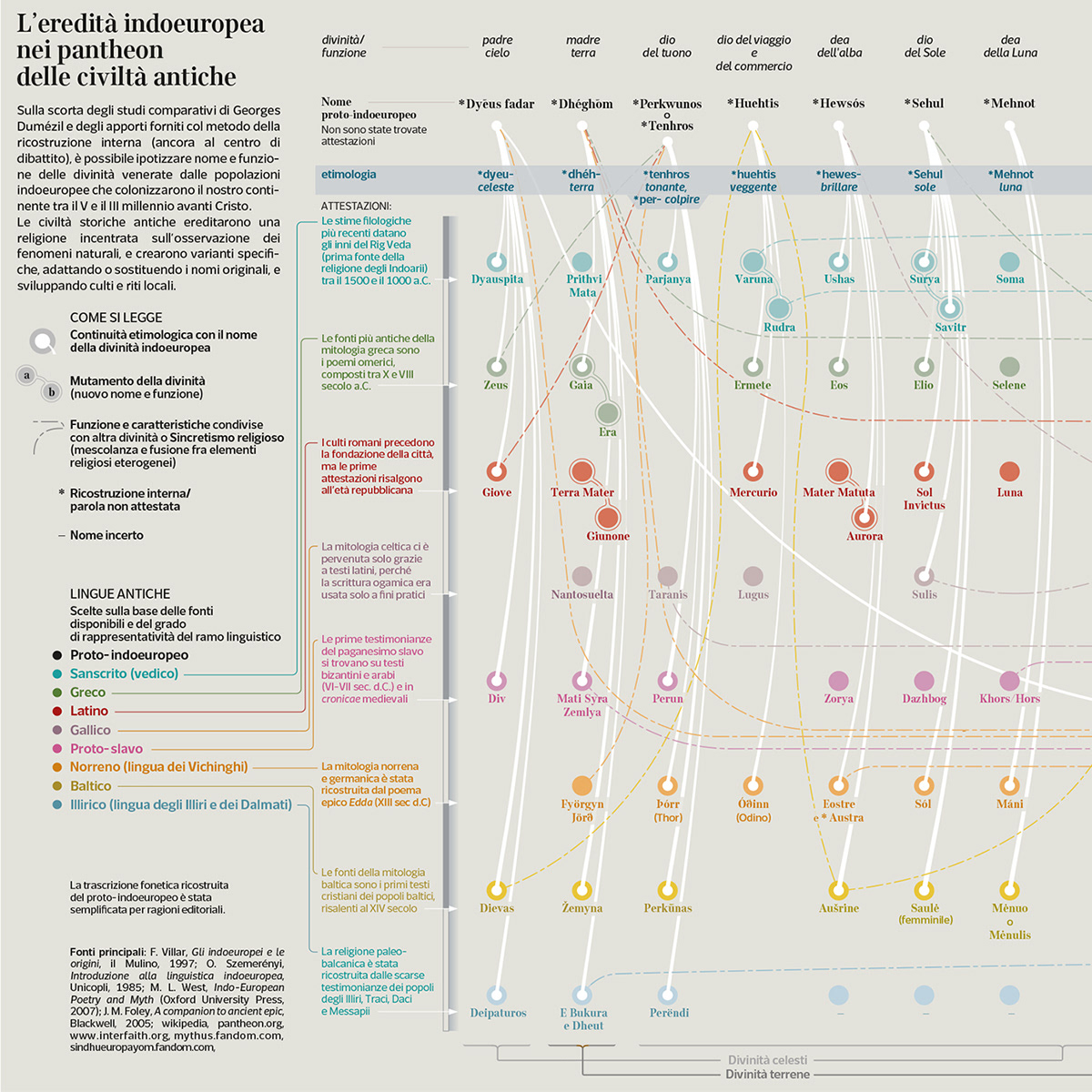

A new visualization for @la_lettura 525 (19th December 2021) about Indo-European religious heritage. It shows the etymological descent of the names of the deities worshiped by some historical civilizations, from those of the oldest Indo-European pantheon. For each Indo-European deity it is reported the function, the reconstructed name, and, noted in blue, the etymology. The white lines trace the same root in some of the lower names. Dotted lines indicate the syncretistic relationships between related cults or their transformation in history.

Since the dawn of Positivism, and along the last two centuries, the study of the etymological relationships between the ancient historical civilizations and a supposed common ancestor population, Indo-Europeans, raised increasing interest among scholars and archeologists.

But the Indo-Europeans, who probably came down to Europe from the steppes of present-day Ukraine in multiple migrations, from 5th to 3rd millennium b.C., left no archaeological remains.

One of the methods available to historians to reconstruct any relationships is internal reconstruction, which is a particular branch of diachronic linguistics that deals with comparing prooves found in later languages, obtaining possible evolutionary lines, and reconstructing the fragments of a lost language.

Nowadays, we the successors of Indo-Europeans are spread among 5 continents and speak a multitude of languages that are not mutually understandable. We've lost the awareness of our unity.

However, the reconstruction of a unique Indo-European religion, among a few other topics, still can give us some shards of knowledge regarding our roots. In Indo-European studies, particularly with regard to religion, there are two opposing tendencies, one optimistic and one pessimistic. While the optimists, among whom Dumézil stands out, describe in detail the various Indo-European deities and their functions, even their structured organization, the pessimists think that we can know almost nothing about the Indo-European religion and its deities.

One of the most important arguments of the pessimistic school consists in demonstrating that historical languages have in common only the proper name of a god, usually the supreme god of their pantheon and that this would only allow the identification of a single divinity of the original people. The word is *dyéus (Sanskrit Dyáuṣ, Greek Zéus, Latin Iovis but Dìovis in archaic Latin, and related to these forms Old Norse Tyr, Old Saxon Tiwes, Old High German Zio). This name *dyéus is usually accompanied by the word 'father': *patér, as in Sanskrit Dyauspita, Greek Zèus patèr, Latin Iùpiter.

Optimists argue that the name should be associated with the function that the divinity performed in each specific civilization, and in some cases also with the symbolism associated with its worship. This way, many connections can be established.

There are risks of underestimating or, on the contrary, overestimating the few records attested in both positions: from the excessive weight attributed to the meaning (an error that pre-scientific etymology typically ran into), to the arbitrary backdating of all etymologies up to a single date, when it is probable that the waves of Indo-European colonization were at least three, in the span of 1500 years.

Optimists argue that the name should be associated with the function that the divinity performed in each specific civilization, and in some cases also with the symbolism associated with its worship. This way, many connections can be established.

There are risks of underestimating or, on the contrary, overestimating the few records attested in both positions: from the excessive weight attributed to the meaning (an error that pre-scientific etymology typically ran into), to the arbitrary backdating of all etymologies up to a single date, when it is probable that the waves of Indo-European colonization were at least three, in the span of 1500 years.

Ancient historical civilizations inherited a religion focused on observing natural phenomena (such as the sun, fire, lightning, thunder, wind, etc.), and created specific variants, adapting or replacing the original names into new cults.

It appears probable that a people from the steppe, formed by shepherds and at the mercy of rain and storms, together with their cattle, practiced the cult of the sun as they needed its rays, the cult of fire because they craved its warm and protection from predators, and worshipped other deities capable of administering the rain, controlling the wind, illuminating the darkness. Some of these cults soon turned into local rites; others lasted much longer among some populations, up to historical times, as in the case of the sun among the Germans and the ancient inhabitants of Scandinavia, or its stylish representations such as the svastikas (the name has Sanskrit origin indeed) which later turned into meaningless emblems in the riverbed of various historical religious traditions.

Personification is probably the process that led to the constitution of the whole sky in a divinity father, and consequently of his conversion in a mother (mother earth) considered as the other half of the universe. Similarly, in sons and daughters deities all the minor natural manifestations contained therein. This is evidenced by the probable etymology of the generic name 'god', PIE * deiwos: Sanskrit devás, Avestian daeva, Latin deus, Old Celtic Deva, Lithuanian Dièvas, Old Norse Tivar (plural). * deiwos is nothing more than an adjective, that gave the name of the father god / celestial vault * dyéus; we could translate it as 'celestial', not in the transcendent sense (so, not 'heavenly') but in the 'atmospheric' sense.

It appears probable that a people from the steppe, formed by shepherds and at the mercy of rain and storms, together with their cattle, practiced the cult of the sun as they needed its rays, the cult of fire because they craved its warm and protection from predators, and worshipped other deities capable of administering the rain, controlling the wind, illuminating the darkness. Some of these cults soon turned into local rites; others lasted much longer among some populations, up to historical times, as in the case of the sun among the Germans and the ancient inhabitants of Scandinavia, or its stylish representations such as the svastikas (the name has Sanskrit origin indeed) which later turned into meaningless emblems in the riverbed of various historical religious traditions.

Personification is probably the process that led to the constitution of the whole sky in a divinity father, and consequently of his conversion in a mother (mother earth) considered as the other half of the universe. Similarly, in sons and daughters deities all the minor natural manifestations contained therein. This is evidenced by the probable etymology of the generic name 'god', PIE * deiwos: Sanskrit devás, Avestian daeva, Latin deus, Old Celtic Deva, Lithuanian Dièvas, Old Norse Tivar (plural). * deiwos is nothing more than an adjective, that gave the name of the father god / celestial vault * dyéus; we could translate it as 'celestial', not in the transcendent sense (so, not 'heavenly') but in the 'atmospheric' sense.

Many studies have been published on the basis of Dumézil's famous functional tripartite division of the pantheon, corresponding to a similarly organized society. From sacrificial rites to funerary cults, to the cyclical conception of life.

(based on F. Villar, Los indoeuropeos y los orígenes de Europa. Lenguaje e historia, Italian edition, 1997)

(based on F. Villar, Los indoeuropeos y los orígenes de Europa. Lenguaje e historia, Italian edition, 1997)